Abercrombie & Fitch

The retailer once catered exclusively to the outdoorsman. Former A&F model BROOKE GOODMAN explains why their newest customer will be the most elusive catch of all.

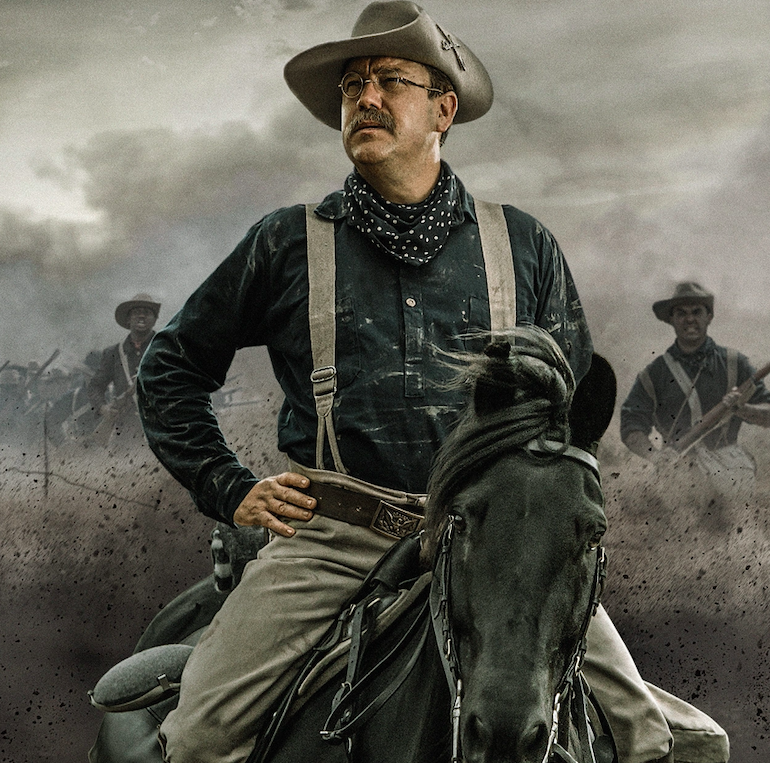

Theodore Roosevelt via National Geographic

It was called “A Man’s World” in 1892 when David Abercrombie created an “outfitter for the elite outdoorsman” in New York City. The retailer outfitted President Theodore Roosevelt for safari. Rear Admiral Richard Byrd for an expedition to Antarctica. Even Ernest Hemingway was a regular. It can fairly be said that the cast of gritty male characters from within the greatest American novels were all suited and inspired by Abercrombie.

At the outset of 2020, Abercrombie & Fitch was strong. 22.5K employees operated 1,049 locations worldwide, and while their operating revenue exceeds US $3.4B the hidden value lied in the company’s assets. Unparalleled for most retailers, A&F holds US $1.2B in equity. Responding to the Covid-19 crisis CEO Fran Horowitz said, “We’re committed to preserving our team’s ability to respond quickly to the rapidly evolving conditions, and positioning A&F to return to growth after the pandemic.”

If “responding to evolving conditions” is the ethos of every big game hunter, it’s an uncanny instinct at Abercrombie & Fitch, too. When Ezra Fitch, in fact, a wealthy lawyer and real estate developer in Manhattan bought a significant interest in the business in 1900, he wasn’t satisfied exclusively selling sporting goods to men. He saw and courted a newly emerging consumer further upstream — women.

The Female Economy

Abercrombie and Fitch became the first store in New York City to supply clothing to both men and women, and after moving to the Financial District, ostensibly to cater to men, the store quickly relocated to the more fashionable Madison Avenue and began focusing on womenswear.

At the dawn of the 20th century, all retail transactions were local. American men, in particular, relied solely on their General Store for a narrow selection of goods and services. Sears, however, upended local merchandisers by sending a comprehensive 532-page catalogue of goods and services to every home in America. Monthly sales were upwards of $1M ($25 million today) and confirmed that women were doing the buying. Macys, the world’s very first department store, was completed in 1902 and pushed women’s shoes and accessories to the front door. Abercrombie, however, was already two years ahead of the game.

The biggest revolution of the 20th century — women’s suffrage, the right to vote, education, labor and equality — created a shift in consumer spending onto themselves. The advent of television, and programing directed at children, would change that direction yet again.

The Youth Market

Children and teens became influencers of household income in the 1950’s when television programming, product placement, and advertising increasingly catered to youth. The term “Pester Power” was a marketing term on Madison Avenue, and by 1970 the Association of National Advertisers declared Youth Markets “the single most important consumer group in the country.”

Youth markets hit their apex in the 1980’s. Surveys showed that Americans were spending more time in malls than anywhere else except home, job, or school. They made 7 billion trips in and out of shopping centers every year, and by 1985 there were more than 26K shopping centers around the country with sales surpassing $1 trillion.

As technological advancements and the ever-expanding cyber landscape became an advertising playground, retailers and consumers were becoming virtual neighbors. Reaching an audience was becoming easier than ever before, and the advent of cable networks launched the 24-news cycle. MTV, Reality Shows, and the Home Shopping Network not only informed and facilitated fashion trends in Madonna’s material world, they effectively conflated American society with consumerism.

Abercrombie & Fitch was nearly 100 years old, and the New York retailer was struggling with lower priced competition while trying to maintain its image. Cash flow problems forced them to first cut inventory, file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and finally sell their name and mailing list for $1.5 million. Limited Brands acquired the company first as a subsidiary, then transformed it into a separately traded company. By simply rebranding their less profitable stores such as — Structure, Express, The Limited — the newly christened Abercrombie & Fitch boutiques now had an instant presence in every mall in America. Shifting their focus to young adults and teens, Abercrombie’s ‘second act’ was becoming one of the largest apparel firms in the United States.

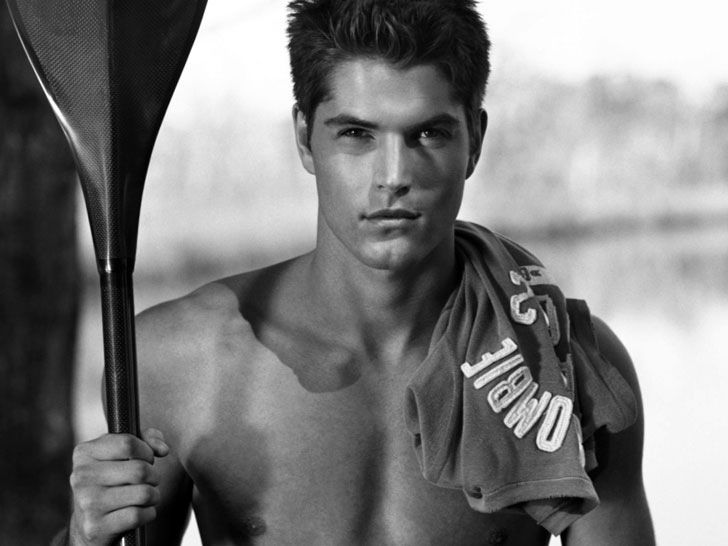

Nick Bateman via Esquire

The Exclusivity Market

Abercrombie wasn’t subtle in marking its territory to teens when they serenaded millennial’s through steamy ad campaigns and immersive store designs. Mike Jeffries in his maiden speech as CEO said “We hire good-looking people in our stores. Because good-looking people attract other good-looking people, and we want to market to cool, good-looking people. We don't market to anyone other than that.”

The company's "Look Policy” was a highly specific set of guidelines for employees which included rules and conditions on everything from physique, body type, and physical attractiveness. Abercrombie was shameless when it came to creating an elitist culture within the youth market. Jeffries continues. "In every school there are the cool and popular kids, and then there are the not-so-cool kids," he says. “Candidly, we go after the cool kids. We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. A lot of people don't belong in our clothes, and they can't belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.”

Yet selling luxury goods to a youth market is an economic non-sequitur. The premise and conclusion are mutually incompatible. Children, teens and youth in general do not have an income, in their own right, nor can working middle class parents provide them with anything more than a modest expendable income. Each child on average spends only $50 per visit on apparel, according to the Consumer Protection Agency, which meant the hidden value at Abercrombie & Fitch came from its breathtaking volume.

Looking Backward

In economics, there are only three types of goods. Necessary Goods are nonnegotiable (food, shelter, clothing). Inferior Goods disappear in the presence of wealth (lottery tickets, no-name brands, public transit), and Luxury Goods represent that which others can’t afford (private education/health care/planes, immoderate real estate, antiques/art, rare foods, fine wines).

The economist John Maynard Keynes once said, “Luxury goods are the means by which the working middle class measure their value in society.” The $18,000 Gold and Onyx Chess Set, for example, stationed audaciously amongst the otherwise affordable fishing rods and riffles in the original Abercrombie and Fitch, was designed to bait and create the luxury consumer of the day. If the average American worker earned $12.98 per week in 1900, and brought home on average $700.00 per year, it would have only taken a scant 25 years to save up for your very own Gold and Onyx Chess Set. Ezra Fitch, a real estate mogul in Manhattan, knew how to both lure and net the working middle class.

The concept of using a card for purchases was first described in 1887 by Edward Bellamy in his utopian novel “Looking Backward,” but when Ezra Fitch became a partner in 1900 he ensured that every customer had their very own ‘charge-a-plate.’ Every male customer, that is. It comes therefore as no surprise that of the 200+ Gold and Onyx Chess Sets sold at Abercrombie & Fitch between 1900-1910, all were purchased on credit. Keynes continues. “It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the American standard of living was bought on the installment plan.” But there was dark side to this debt. For a brand built around an elitist image by nature isolates and discriminates.

The advent of the internet and home computers in the mid-90’s coincided with Jeffries tenure at A&F and pioneering social media platforms such as MySpace enabled retailer and consumer, now in active dialogue with each other, to engage in a 24-hour merchandising narrative ad nauseam. As A&F continued to push the envelope toward their pampered, self-entitled and privileged customer of the 1990’s, it was only a matter of time before they’d be forced to glance in a mirror. As A&F passed its first 100 years as an American retailer, it was about to be held accountable by the very customer they’d been courting — the Millennials.

This is Abercrombie & Fitch

I joined the management team at Abercrombie and Fitch in 2012. It was a chance encounter with a company who’d targeted me as a consumer, and, after my post-graduation plans went sideways, somehow engaged me as a last resort and member of their team.

As class-action suits were being filed against the company for alleged discrimination against African Americans, Asian Americans, and other minority applicants in 2003, it was widely reported that A&F managers were ordered to “deny a store was hiring if applicants didn't fit a certain look,” according to Business Insider. The company settled the lawsuit in 2004, without admitting any wrongdoing, paying out $40 million to the plaintiffs.

By 2006, the company was drawing widespread criticism from celebrities like ABC’s Ellen DeGeneres and her 4+ million viewers, and in 2012 another lawsuit emerged and was settled for age discrimination. By 2013 the once bold and belligerent Jeffries was tapping out conciliatory Facebook posts that read, "I sincerely regret that my choice of words was interpreted in a manner that has caused offense." A year later he was ousted.

CEO Fran Horowitz and I had joined A&F during the same time frame, and with her came racks of plus sizes and a waft of e-mails about diversity and inclusion. As a recruit, however, I was among the pawns within the brand’s cliché. After purchasing my AAA’s (seasonally approved items) and completing a 12-week Manager-in-Training program, I was literally dressed in the brand and fully instructed how to flaunt it. Every sentence of A&F’s new “Culture and Values” mission began with the word “We.” The new and improved “we hire smart, humble, hardworking people” was re-worded to replace “we hire good looking people” though store operations were not vindicating original criticisms and lawsuits as yet.

Not until January 2013, that is, when store employees were first invited to participate in an Inclusion Challenge; which invited us to “show how being more open, approachable, and collaborative can impact the business of our brands, how it connects to retention of our associates, and creates an inclusive environment.” I submitted an essay sharing a very personal experience and was recognized as a finalist. It was my first experience with corporate turning lip service and script into standards and practices.

Jeffries’ infamous interview had resurfaced that summer, refueling an uproar against the brand, and reminding the company of an 11 straight quarter sales decline and waning customer. Indeed, sales had been falling for years, and the company had reached another tipping point with yet a new consumer: Generation Z.

By 2015, Horowitz began knocking down provincial marketing barriers in their behalf. Floor staff, for example, would no longer be referred to as “models.” Interview guidelines were re-written. They even dropped their controversial Look Policy. Employees were no longer coerced into purchasing A&F clothing and merchandise to avoid violations, and stores began shifting their focus from seductive sensory overload to authentic customer engagement. Size runs were expanded for both sexes, and by 2016 corporate began growing their ‘Diversity & Inclusion Division” for which I flew to Ohio to interview. Horowitz at the helm, rudder and sail were slowly turning.

By 2018, the company was focused more than ever before on the digital natives. Horowitz’ new policy push around diversity and inclusiveness was aimed expressly at a market A&F called “Abercrombie Teens” and “Abercrombie Kids” respectively. Seemingly noble, A&F’s new and improved mantra was directed at a highly tech savvy consumer; whose now global visibility and engagement with one another was effectively eviscerating exclusionary barriers with everyday connections.

If Jeffries' exegesis led to lascivious campaigns and exploitation, Horowitz was summarily trotted out to lead the crusade of diversity and inclusion. In fact, sales at A&F soared upward of $1 billion in 2019’s second quarter, according to the Quarterly Earnings Report, all thanks to repacking a new conversation, with a calculating message, on a targeted new consumer group.

Enduring Style, Always Evolving

The new and improved Abercrombie & Fitch no longer discriminates against African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and women by preferentially offering floor sales and store management positions to Caucasian males (González v. Abercrombie & Fitch, 2004). Nor do they require their Muslim employees to remove their hijab, or other religious garments, in accordance with their Look Policy (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Abercrombie & Fitch, 2009). The disabled are no longer forced to work in the stock rooms, or out of sight of customers (Riam Dean v. Abercrombie & Fitch, 2009), nor are their valued customers videotaped by employees while in dressing rooms (Minnesota Department of Human Rights v. Abercrombie & Fitch, 2010).

Alas, there aren’t even any more shirtless models at store openings. For of the $1 billion dollars in revenue that A&F garnered during the second quarter of last year, its well to know that upwards of 80% of that revenue came from online sales. Store fronts and salespeople are disappearing into our virtual identities, and Section 230 — a 1996 federal statute that absolves all internet companies from any liability of their Users — has enabled the abject loss of social deference from their new online shopper that CEO Fran Horowitz rightly observes is “ever evolving.”

Amelia Earhart via History.com

Afterword

When Amelia Earhart left the ground in 1937, the first female to fly solo over the Atlantic Ocean, she was draped and dressed in Abercrombie. The truth is, Abercrombie manufactured the clothes men wanted to wear all the time — but didn’t. They were the costumes in which the working middle class dreamed their way into the collective unconscious. “Be as you wish to seem” the aviator’s grandmother once told her. “There’s more to life than being a passenger.”